- The underlying mechanisms that influence limb range of motion and how they mediate flexibility and stretching.

- The ways in which improved limb range of motion not only affects how we move but can also impact longevity by way of preventing or repairing injuries, reducing inflammation, and even adjusting tumour growth.

- The different types of stretching and which one is the most effective for increasing limb range of motion long-term.

- How often to stretch, how long to hold a stretch, and the importance of warming up before a stretching session.

- Strategies for creating an effective and safe stretching protocol tailored to individual goals.

- The role of the von Economo neurons (VENs) and the Golgi tendon organs (GTOs) in how we feel and react to stretching.

- How the enhanced flexibility from practising yoga can shape your brain to increase both physical and mental pain tolerance.

Improve Flexibility with Research-Supported Stretching

Improve Flexibility with Research-Supported Stretching

- Offset the natural decrease in flexibility that comes with ageing, as well as the potential injuries caused by it, by stretching regularly and improving limb range of motion and functional movement.

- When performing resistance training involving pushing and pulling exercises for antagonistic muscle groups, such as chest and back, consider interleaving your sets. Switch between pushing and pulling exercises with a 60-second rest between each set. This can potentially help maintain your repetition numbers better than doing straight sets.

- To enhance the range of motion of a particular muscle group, prioritise static stretching techniques, including PNF (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation). Static stretching has been proven to be more effective in increasing limb flexibility than dynamic or ballistic methods.

- For optimal results in increasing flexibility and improving range of motion ,aim to sustain a stretch for a 30-second. There's no science-backed additional benefit from stretching for longer durations (60 seconds) or increasing the frequency (from one to three times a day).

- Instead of a single, long stretching session, prioritise the total weekly duration of stretching for better results on your range of movement. Aim for at least five minutes of stretching per muscle group per week, spread across five days (e.g. two to four sets of 30-second static holds for each muscle group, five days per week).

- To prevent injuries during stretching, raise your core body temperature beforehand. If you're already warm from activities like running or weight training, perform static stretches at the end of that session. Otherwise, consider warming up for about 5 to 10 minutes with light cardiovascular exercise before starting your stretching routine.

- Consider following the Anderson method in your static stretching sessions. Do not pre-define your range of motion. Concentrate on feeling the stretch in the relevant muscles, and focus on reaching the end of your range of motion each day whilst taking external factors (e.g. stress, temperature, tension) into account.

- When starting a flexibility programme, avoid pushing into pain. Instead, focus on very low-intensity stretching (around 30-40% of your potential intensity, where 100% is the point of pain) for an effective and safe approach. Gentle stretching, aka Microstretching, can improve lower limb range of motion more effectively than moderate-intensity stretching.

- Consider taking up yoga not only as a tool to learn movements and increase flexibility but also develop the ability to control your nervous system and enhance pain tolerance.

How Our Limbs Respond to Stretching

We all lose flexibility with time. For most of us, this decrease starts around age 20 and becomes more dramatic until around age 49, continuing at a rate of approximately 10% every 10 years. Incorporating flexibility exercises into your routine is a great way to maintain — and potentially improve — your range of motion (ROM), thus reducing the risk of injury.

But before delving into stretching practices, it’s essential to understand what systems and features contribute to our flexibility. After all, something has to determine just how far our limbs stretch.

This something is a collective effort between nerves and muscles, which work together to make sure our joints and limbs move in a safe way. There are two main mechanisms for how this happens.

The first happens with the help of intrafusal spindle fibres, which are responsible for communicating muscle stretch to the spinal cord and brain. If they sense that the stretch is excessive, they activate specific motor neurons that cause the muscle to contract. The second protective mechanism is like a weight sensor, and it is facilitated by the Golgi tendon organs (GTOs). If we try to lift something too heavy, the GTOs signal the spinal cord to prevent our muscles from working too hard, helping to prevent potential injuries.

Another important player in our body’s safety and control system is a part of our brain called the insula; it helps us understand our body’s sensations, like pain and comfort. Inside the insula, there are special cells called von Economo neurons. These neurons help us decide whether to relax or push through discomfort, and can even aid in ignoring pain when needed.

All these mechanisms are already in place. But they can be used strategically to improve limb range of motion and flexibility.

The Different Types of Stretches to Increase Limb ROM

There are several methods of stretching to improve flexibility and limb range of motion efficiently and safely. They are generally grouped into dynamic, ballistic, static, and PNF (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation) stretching. Dynamic and ballistic stretching involve controlled movements with some momentum, whereas static stretching holds a position without momentum. PNF stretching is more complex: it combines stretching with resistance and relaxation techniques, using neural feedback from muscles and joints. These techniques can be adjusted for active or passive stretching and can use tools like straps or weights for added effect.

Slowly bending over at the waist and trying to touch your toes or putting your hands to the floor and then holding that end position before coming up in a slow and controlled way, such that you reduce the amount of momentum to near zero would be one example of static stretching.

Andrew Huberman

Creating An Effective Stretching Protocol for Long-term Results

According to scientific studies, whilst dynamic and ballistic stretching have their merits in specific contexts, static stretching, including PNF stretching, are the most effective strategies for enhancing flexibility and ROM in the long-term. The frequency, duration, and intensity of stretching sessions play a pivotal role in achieving optimal results.

Research suggests that dedicating at least five minutes per week to stretching is fundamental for improving ROM. In terms of sets and holds, studies indicate that performing two to four sets of 30-second static stretches, five days a week, is a key parameter for significant gains in limb flexibility.

Last but not least, warming up before a stretching session is important to prevent injury. If you’re already warm from activities like running or weight training, performing static stretches at the end is beneficial. If not, a 5 to 10-minute easy cardiovascular exercise can effectively warm up the body for stretching.

Protocol #1: Static Stretching

| Stretch | Static Hold (per side) | Sets | Order | Description (Repeat on other side) |

| Standing Quadriceps Stretch | 30 seconds | 3 | Alternate | Stand up tall and shift your weight to the R. leg. Lift your L. foot and grasp it with L. hand. Pull your L. foot toward your glutes until you feel the stretch in your quads. |

| Standing Hamstring Stretch | 30 seconds | 3 | Alternate | Stand upright with the spine in a neutral position. Place the R. leg in front of the body with the foot flexed, heel pushed into the ground, and toes pointing toward the ceiling. Slightly bend the L. knee and gently lean forward until you feel the stretch in you R. hamstring. |

| Figure 4 Stretch | 30 seconds | 3 | Alternate | With your back on a mat, bend your knees and plant your feet hip distance apart on the mat. Cross your R. leg over your L. thigh, placing the outside of your R. calf just above your L. knee. Allow your R. knee to open outward and pull your L. thigh toward your abdomen and hold. |

| Supine Spinal Twist | 30 seconds | 3 | Alternate | Lie on your back and hug your R. leg into your abdomen. Place your L. hand on your knee and extend your R. arm along the floor at shoulder height. Draw you R. knee over to your left side. Aim to keep your R. shoulder on the floor and turn your head to the right. |

Figure 1: Huberman Lab Static Stretching Protocol

Source: https://hubermanlab.com/stretching-protocols-to-increase-flexibility-and-support-general-health/

The Anderson Method of Stretching

Just like there are different categories of stretches, there are different techniques for going about it. The Anderson method introduces the idea of pushing through discomfort during stretching and focusing on the feel of the stretch rather than fixating on achieving a specific range of motion. This technique involves stretching to the end of one’s range of motion and concentrating on the sensation in the muscles being stretched. In fact, this model is in line with some recent research, which suggests that low-intensity stretching, conducted at around 30-40% of the point of pain, can be more effective than moderate-intensity stretching for improving flexibility.

Stretching Beyond Flexibility

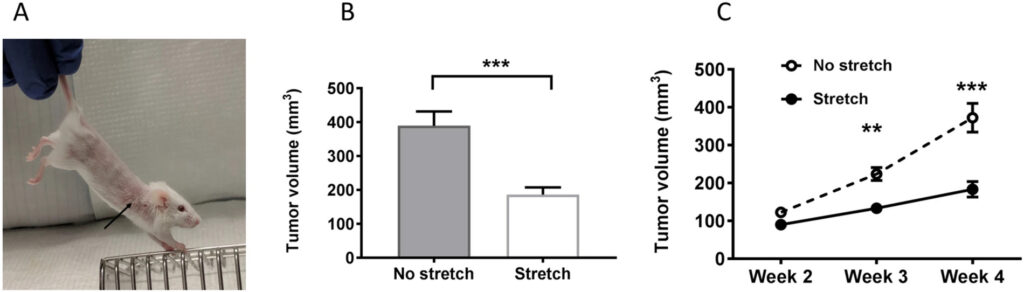

But there is more to stretching than physical benefits. Studies show that stretching activates the parasympathetic nervous system — a network of nerves responsible for slowing our heart and breathing rates and promoting a state of relaxation. This relaxation response can potentially reduce inflammation and even impact tumour growth. In fact, a study conducted on mice revealed that daily stretching led to a significant reduction in mammary tumour growth, highlighting the interplay between stretching, relaxation, and the immune system.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-26198-7

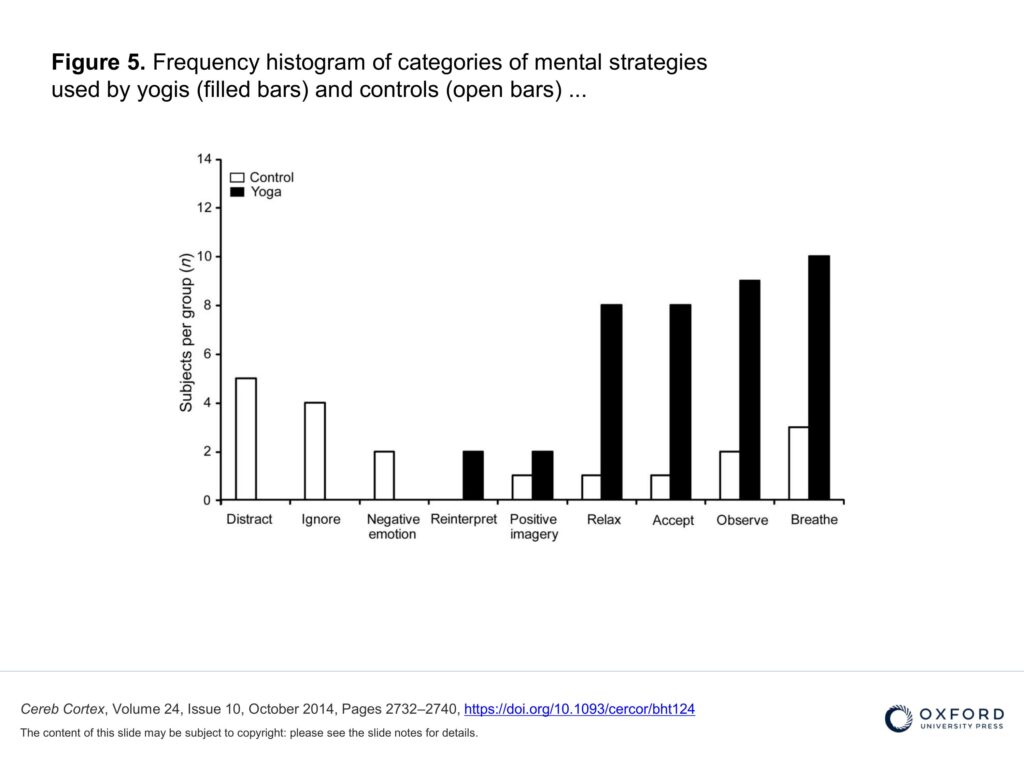

The Role of The Insula & Yoga Practice

Most of us associate yoga with flexibility. And whilst that’s very much true, yoga practice also has a huge impact on our brain. In particular on the insula, a brain region associated with interoceptive awareness and pain processing. A recent study found that long-time yoga practitioners had increased grey matter volume in the insula, and demonstrated greater pain tolerance than control subjects. This was mainly achieved because yogis tended to use mental strategies (such as positive imagery, relaxation techniques, and focused breathing to cope with discomfort) when stretching, reshaping their relationship with pain and flexibility.

Source: https://academic.oup.com/cercor/article/24/10/2732/307000

This tells us two things. First, that the practice of stretching can rewire our neural circuits, enabling us to better cope with discomfort, enhance flexibility, and foster holistic well-being. Second, that if you’re like most people and tend to neglect stretching, there are plenty of reasons to reconsider.